1.

In Invisible Cities, a short novel by Italo Calvino consisting of dialogues between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan, we find this:

“The hell of the living is not something that will be: if there is one, it is what is already here—the hell where we live every day, that we form by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the hell and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and learning: seek and be able to recognize who and what, in the midst of the hell, are not hell, then make them endure, give them space.”

2.

We’ve passed the point where we merely acknowledge how bad things are—how broken, how unprecedented, etc, etc. We crossed the threshold we resisted for so long. The version of hell (for many) is here. It has been here. As Calvino wrote—there is still, even in hell, agency, choice, perspective. Something I’ve been thinking about lately is: Who do I want to be in the brokenness? Who can I be in the brokenness?

3.

When I was around my daughter’s age—9, almost 10—if you had asked me what I wanted to be, I’d tell you, hands on my hips with all the certainty that age can offer: “I’m going to be a journalist.” I’m not exactly sure where I got that idea from, perhaps because I liked watching the 8 p.m. news with my father. Journalists, to me, were people who knew what they were talking about. I liked writing, history, social sciences, and listening to adult conversations. If you gave me more time, I’d probably also tell you I was a ballet and contemporary dancer, since I was six years old. There was also some obsession with archaeology (?!). I’d tell you I was a singer, putting a kitchen rag on my head secured with a tiara to mimic long, straight hair, twisting and turning in the living room. And I definitely had the teacher phase—lining up all the toys on the ground and speaking in a loud voice to my imaginary classroom.

Fast forward to just before college—it didn’t occur to me to get a Bachelor’s degree in any of these interests. Nobody I knew had ever done that. I decided to go with something more “practical”—something in business or administration—but really, what I wanted was to travel the world, dance and be near art as much as possible. During those four years of college, I spent time sneaking around the floors where they held the dance classes— the big rooms with mirrors, dancers hanging around in their leotards stretching in the hallways. So different from my classmates, yet so familiar to me. I spent years visiting those floors, wishing they were mine, but not feeling quite ready to claim them. Almost as if they were only meant for admiration—from a safe distance.

From the certainty of wanting to be a journalist, to the “wrong” bachelor’s choice, I became many other things. I lived in many other places. I lived in Mexico City. I went on to study a Master’s in Arts and Culture Management in Barcelona. I worked in various jobs, like so many do. Certainty began to give way to curiosity. Time expanded my ideas of who I was—and who I could become. My sense of self became something malleable, like kids’ Play-Doh: sometimes a circle, sometimes a snake, sometimes a cube, and other times a ball.

Not to make this longer than it already is—in 2011, I moved to Los Angeles. And yet again, I was at the beginning of something new. If I ever had an identity, it got completely stripped down. I went to the bottom, beyond the bottom. The LA chapter—which is still unfolding—was hard, challenging, at times a slap in the face, and other times felt like a firm, loving teacher. It keeps sitting me down and asking: Who do you want to be during this chapter of your life?

I worked in the arts. I moved away from the arts. I moved away from myself. I went back to school. I got certifications. I returned to dance. I returned to myself. I returned to my body. I created a family. I had a baby. I became a mother. I continued to dance. I became a teacher. I started ideas. I failed. I took photos. I traveled. I cried on the freeway. I improved my cooking. I volunteered. I made new friends—again. I had to learn how to write in a different language. I got a cancer diagnosis. I went through treatment. I started to lift weights. I learned about finances as if I were studying a foreign dialect. And now, I’m back in school again, finishing my Master’s in Psychology.

I don’t know what’s ahead, but what I’ve learned from being like dough is this: allowing myself to be who I need to be in each chapter of my life is my compass. In some ways, I still recognize that 8-year-old girl, so certain of herself. And in other ways—especially in changing times—I’ve had to learn to let mystery surprise me.

4.

The other day, I was having a conversation with my brilliant friend Nicole, and she said something that released the pressure in my jaw and in my chest: “Identity can sometimes be a prison.” We were talking about the times we’re living in—how they ask us to pivot, to adapt and to transform in chaotic circumstances. We talked about what we’re willing to put down, what we’re willing to turn toward, what parts of us we can let go of, and what parts need to sit at the head of the table.

In theory, all of this might sound simple. But in practice, it can be incredibly hard—especially for those of us who grew up as extensions of someone else (like a parent, for example), never really knowing who we were, trying to find that answer in other people or other places. There’s a certain rigidity that comes with feeling confusing of our identity, or of protecting who we are—or who we think we are. And that rigidity, I believe, is worth examining when change is all around us.

When we find ourselves paralyzed or numb in the face of transformation—in the face of hell—it’s worth exploring why we grip rather than release. There’s something old in us that needs to grasp onto a concrete belief or internal experience—because anything other than that feels far too risky, far too scary. But as we’re tired of knowing by now: it’s often the resistance that hurts the most.

5.

“I am large, I contain multitudes.” Whitman wrote this poem in 1855, as a bold celebration of individuality, the human body, nature, and the interconnectedness of all life. It first appeared as part of his collection Leaves of Grass, and it marked a radical departure from the poetry of the time—it was free-flowing, expansive, and unapologetically democratic in spirit. Whitman wanted to create a new kind of poetry that was distinctly American—one that spoke in the voice of the common person, embracing the diversity, physicality, and raw energy of life. He believed the divine could be found in every person and every blade of grass, and that poetry should reflect that truth. Whitman remind us that we can be larger than we thought, and in the process of transformation, we gain more than we lose. We gain a multitude inside of ourselves.

6.

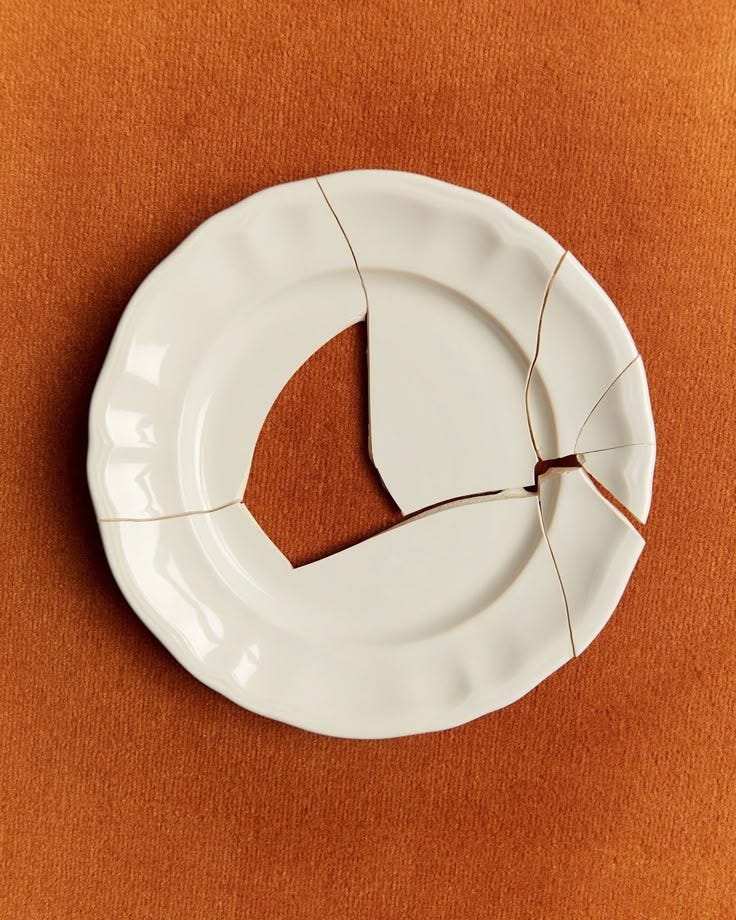

In my last newsletter, I shared a reflection on living in brokenness:

“I’ve been reflecting—from my Southern Hemisphere/Latin American perspective—on what it means to live in America now. It seems that what we are being called to do, or to learn to do, is to live in the brokenness. There is an ingrained idealism in American culture that hinders us from truly facing reality as it is—not as it used to be or as we wish it to be.

Coming from a place that has always known how to exist in brokenness, I feel compelled to share this: there is resistance in standing in your dignity and joy, in your beauty and aliveness, in your grief and despair—even in times like these. Especially in times like these.”

A few people replied asking for more insight on this. Not that I necessarily have more—perhaps this is simply the lens through which I see the world. Coming from a place like Brazil—imperfect and paradoxical—we had to learn very early on what it means to live in change. Constantly. We understood that brokenness was the baseline, so to speak. And when I say brokenness, I don’t only mean it in a negative way. I mean the literal state of things being broken—systems that aren’t fixed or perfect. I also mean that in brokenness, there are cracks, and in those cracks, there are openings. That’s where we find reality—as it is, not as we wish it were.

From that place, there’s a certain kind of honest freedom. A freedom to become really good at dancing with life, discovering what you want to be, what you can be. Brazilian people, for instance, decided they would work hard, adapt, persevere and also be joyful. They would enjoy life to the fullest and live with faith—despite it all.

I was born during a dictatorship—at the tail end of it. My mother, while pregnant with me, was out in the streets demanding elections, calling for democracy. It took a few years, but Brazil found a way forward.

Now, living in the U.S., I often have to look back—to my ancestors, to the place and time I came from—to remember how to live here, now. By looking back, we can learn how others found their way forward in unprecedented times.

7.

Who do I want to be in the brokenness?

Who can I be in the brokenness?

8.

Our capacity to tolerate change is closely tied to our capacity to tolerate discomfort, uncertainty and, fear. And that, in turn, is deeply related to our ability to not take ourselves so seriously, to release the need to prove anything, to let go of rigidity and a fixed identity. All of that is connected to a spacious sense of self who is steady while also curious and adaptable. This softening or this peeling is what allows for freedom—a wide-open kind of freedom, where we can contain our multitudes. But we don’t do that in a bubble. We do it in relationships. We let people see us trip, fall, get up again, and try. We let others witness our cracks.

When we occupy our multiplicity, we are also occupying the spaces in between ourselves—the capacity to say, “I don’t know who I am in this phase of my life, but I am willing to find out.”

And I get that for so many, this can feel close to impossible. But what if the point is simply in the asking of the question? Perhaps what I want to say is that there’s value in the willingness itself—in the pause, in the not knowing, in the brokenness. What if the point, during broken times, is less about holding onto a fixed version of ourselves, and more about softening into the truth of who we are right now? To allow space for the parts that are still forming, still stretching, still unsure to surface. To not rush the becoming. Identity isn’t just a destination—it’s a rhythm, a relationship with life itself and freedom isn’t found in knowing exactly who we are, but in allowing ourselves to be as many as we want to be - especially in the brokenness.

With Love,

Mariana

A Surprising Route to the Best Life Possible

A playlist for the broken times

Entering the Challenge Zone with Pema Chodron

2 poems read by Pádraig Ó Tuama: When in doubt by Sandra Cisneros &

David Whyte is someone who helps me remember something about myself. Here’s a beautiful conversation: part 1 / part 2

If these themes resonate with you and you are interested in a deep, more personal experience, I support individuals, teams and new teachers in different capacities. If you need more information, you can find it here:

In three words I can sum up everything I’ve learned about life: it goes on.

-Robert Frost